Science and Technology

Democracy Is Ailing. Here’s How We Can Start Reviving It

by Vanessa Bates Ramirez

Tue, 17 May 2022 14:00:15 +0000

Masks. Vaccines. Immigration. Abortion. Gun control. Taxes. The list of divisive issues in American politics goes on, with liberals and conservatives seeming more polarized and less able to agree than ever before. Indeed, democracy is in a fragile state, not only in the US but around the world. What’s gone wrong to get us into this sorry situation?

In an enlightening discussion last week at the Chicago Humanities Festival, two thought leaders posited an unexpected response: it’s not so much that we’ve messed things up—it’s that we’re in the midst of an unprecedented democratic effort, and there are bound to be some bumps in the road. Moreover, if we want the future to look bright instead of dim, we need to start working harder to bridge societal divides.

Yascha Mounk is a German-American political scientist, professor of International Affairs at Johns Hopkins University, senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, and the author of four books, the most recent being The Great Experiment: Why Diverse Democracies Fall Apart and How They Can Endure.

Dr. Eboo Patel is the founder and president of Interfaith America, a Chicago-based international nonprofit that aims to promote interfaith cooperation. He’s also the former faith advisor to President Obama and author of four books, most recently We Need to Build: Field Notes for Diverse Democracy.

According to Freedom House’s 2021 ‘Freedom in the World’ report, the world has entered the 16th year of a democratic recession, and the international balance has shifted in favor of tyranny. What has caused democracy to become so fragile, and are we at some kind of precarious turning point?

Delicate Democracy

We’ve come to take it for granted that in relatively affluent countries like the US, Australia, Germany, or Japan, democracy will always be the chosen system of government and is unlikely to come under serious threat. “I started worrying about whether that was really true, because I saw all these signs of fading democratic values,” Mounk said. “People participating less in civil society, the extremes rising, people being more open to populist leaders.” Take Trump in the US, Bolsonaro in Brazil, Modhi in India, or López Obrador in Mexico, to name a few.

This shift, in Mounk’s opinion, has structural reasons, like a stagnation of living standards for middle- and working-class citizens, as well as a rise in internet and social media use, which pulls parties and issues to the extremes. “But it also has to do with the fact that we’re trying to do something unprecedented right now,” he added. “We’re trying to build religiously and ethnically diverse democracies that treat their members as equals.”

When democracies like Germany and the US were founded, they were to a large degree religiously and ethnically homogeneous. The US has become more diverse, but it doesn’t have a history of treating different groups of citizens equally; one group got the power and influence while other groups were excluded.

There’s a widespread pessimism in the US about the state of society—but, Mounk pointed out, building diverse democracies is extremely hard, and it’s gone wrong multiple times in history. “If you understand that, you can look at the changes in US society over the last decade and have optimism,” he said. “Maybe not at a political level, but in the changes you see at the heart of our society. We are actually making real progress towards building these diverse democracies, and we’ll continue to build on that in the coming decades.”

How’s that for a breath of fresh air?

Crucial Civil Society

Patel’s focus is on building civil society: athletic leagues, religious organizations or houses of worship, and other special interest or hobby groups where we spend time outside of our families. “Civil society is the place where people from diverse identities and divergent ideologies come together to engage in common aims and cooperative relationships,” Patel said. “This is the real genius of American society—you have a critical mass of institutions and spaces that bring people together for common aims, and the nature of the activity shapes cooperative relationships.”

Bringing people from different groups together to deepen trust and understanding is key. Groupishness, Mounk pointed out, is part of human nature, and that will never change—but we must manage it in a way that inspires cooperation and friendship rather than hatred, resentment, or violence.

He cited India as a thriving diverse democracy, but with periodic outbursts of violence between Hindus and Muslims. Studies have found that in villages and cities where there’s less violence, there are more civic associations that unite people; Hindus and Muslims are both members of literature clubs, athletic clubs, volunteer organizations, etc. In places where violence more frequently breaks out, these associations still exist, but they keep Hindus and Muslims separate. It’s no big surprise, then, that in moments when tensions are running high, the people in the first group of cities trust each other, while in the second, they don’t feel like they know each other.

This second group, though, has been the rule throughout history; what we’re trying to do now is the exception. “The rule of human history is that identity communities build institutions for their own identity communities to serve, grow, and reproduce them,” Patel said—and, when it comes down to it, to fight other communities.

A brilliance of diverse democracies, he added, is that groups can start institutions that are an expression of their identity—say, a Jesuit university or a Jewish volunteer organization—but serve people from any group. Patel’s own father, an Indian Muslim, came to the US to attend the MBA program at Notre Dame—a private Catholic university—and that’s why Patel is here today.

“That’s the secret sauce of America’s democracy, and I think it’s in danger,” he said. “We have to continue to build spaces out of our own identity expression that connect to other identities and have a stake in them thriving.”

Demography’s Not Destiny

The US Census Bureau has predicted the US will be a “majority minority” country by 2045. If that’s true, Mounk and Patel both said, we’d better start working harder to get away from the polarized, divisive political culture we’re stuck in now.

“We’re at a moment in America where liberals and conservatives don’t agree on anything,” Mounk said. “But there’s one thing they agree on, and it’s wrong and dangerous: that’s the idea that demography is destiny.” In his opinion this is far too simplistic, because the way different demographics vote can change over time.

Catholics and Irish Americans were key for Democrats in the 1960s, Mounk said, but today are one of the most reliable voter bases for Republicans. What made Trump competitive in the 2020 election was that he significantly increased his share of voters among every non-white demographic, from African-American to Asian-American to Hispanic. Biden ultimately won because he increased his share of white voters relative to Hillary Clinton’s share from 2016. “We simply cannot predict who’s going to be winning elections by running those numbers out into the future,” Mounk said. “And that’s a good thing for our society, because I don’t want to be able to look into this audience and know who you voted for by the color of your skin.”

Fixing the Future

Technology has done some damage to democracy, mainly through social media algorithms that amplify the most extreme voices at the expense of moderate, rational ones. What can tech do now to reverse this harm—and go beyond that to revitalize democracy, build meaningful connections between groups, and dial down political polarization?

Patel spoke of the importance of solution-minded entrepreneurs in helping heal social wounds. “A huge part of what makes our society healthy and vibrant is people standing up and saying ‘I’ll solve that,’” he said. “Local solutions to local problems can have massive national implications.”

The democratization of technology, information, and knowledge means there’s a greater proportion of people than ever before with access to tools that can catalyze positive change. We see people using tech to solve issues like homelessness, pollution, climate change, and even making existing digital technologies more ethical.

How can this spirit of community-oriented innovation be applied to fixing and preserving our ailing political system and bridging the many divides between citizens?

A line from Mounk’s book reads, “Never in history has a democracy succeeded in being both diverse and equal, treating members of many different ethnic or religious groups fairly, and yet achieving that goal is now central to the democratic project in countries around the world.”

We’ve got our work cut out for us.

Image Credit: Breaking The Walls / Shutterstock.com

By: Vanessa Bates Ramirez

Title: Democracy Is Ailing. Here’s How We Can Start Reviving It

Sourced From: singularityhub.com/2022/05/17/democracy-is-ailing-not-because-we-broke-it-but-because-what-were-trying-to-build-is-unprecedented/

Published Date: Tue, 17 May 2022 14:00:15 +0000

Science and Technology

Bitcoin’s Blowing Up, and That’s Good News for Human Rights. Here’s Why

Bitcoin’s value reached an all-time high this week after Tesla announced it had bought $1.5 billion worth of the cryptocurrency. After its launch in early 2009, Bitcoin has gone through a lot of ups and downs. Some of its biggest price swings were in 2017 and 2018, when a steep rise followed by an 84 percent decline brought plenty of hype and headlines. After a quiet period, the last three months of 2020 saw yet another sharp rise as the currency’s value more than tripled—and it’s still climbing.

Not surprisingly, more and more investors are now jumping on what can still seem like a techy, trendy bandwagon. In an economy where governments are printing money hand over fist, people want a more secure place to put their assets. In addition to prevailing economic uncertainty, many institutional investors are dipping their toes into the cryptocurrency, and even PayPal began offering customers the ability to buy Bitcoin late last year. Elon Musk’s repeated endorsement of the cryptocurrency hasn’t hurt, either. Some even believe digital currencies like Bitcoin are the future of money.

But intertwined with Bitcoin’s more speculative potential (as an asset or currency) is an important feature many investors may miss: its power to protect human rights and stand against tyranny.

In a new video for Reason magazine, Alex Gladstein, chief strategy officer at the Human Rights Foundation, explains why the cryptocurrency is an inalienable tool for preserving freedom, and how it’s being used by people in different parts of the world to do so.

Money makes the world go ’round, and as such, it’s a perfect tool for surveillance and control. The decline of cash in many societies and its replacement with digital payment methods means we’ve all but kissed financial privacy goodbye; all of our digital transactions are logged and kept on record for years.

In most democratic countries this doesn’t tend to come with consequences much more intrusive than targeted ads. But for the more than four billion people living under authoritarian regimes, it’s a different story.

Their governments can—and do—freeze peoples’ bank accounts, shut down ATMs, decide who gets cut off from financial services, and even seize private funds. Actions like these are often targeted at individuals labeled as problematic: activists, dissidents, union leaders, critics of the ruling party, intellectuals, and the like. Cutting off access to money is a quick-and-dirty way to immobilize people, not to mention wreak havoc when it’s done on a large scale.

If only there was a monetary system not controlled by a central bank, untouchable by governments, where value could be transmitted without corruption or interference and unaffected by international borders.

Enter Bitcoin.

This article first appeared on Singularity Hub and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Image Credit: Aleksi Räisä on Unsplash

Science and Technology

China Wants to Be the World’s AI Superpower. Does It Have What It Takes?

China’s star has been steadily rising for decades. Besides slashing extreme poverty rates from 88 percent to under 2 percent in just 30 years, the country has become a global powerhouse in manufacturing and technology. Its pace of growth may slow due to an aging population, but China is nonetheless one of the world’s biggest players in multiple cutting-edge tech fields.

One of these fields, and perhaps the most significant, is artificial intelligence. The Chinese government announced a plan in 2017 to become the world leader in AI by 2030, and has since poured billions of dollars into AI projects and research across academia, government, and private industry. The government’s venture capital fund is investing over $30 billion in AI; the northeastern city of Tianjin budgeted $16 billion for advancing AI; and a $2 billion AI research park is being built in Beijing.

On top of these huge investments, the government and private companies in China have access to an unprecedented quantity of data, on everything from citizens’ health to their smartphone use. WeChat, a multi-functional app where people can chat, date, send payments, hail rides, read news, and more, gives the CCP full access to user data upon request; as one BBC journalist put it, WeChat “was ahead of the game on the global stage and it has found its way into all corners of people’s existence. It could deliver to the Communist Party a life map of pretty much everybody in this country, citizens and foreigners alike.” And that’s just one (albeit big) source of data.

Many believe these factors are giving China a serious leg up in AI development, even providing enough of a boost that its progress will surpass that of the US.

But there’s more to AI than data, and there’s more to progress than investing billions of dollars. Analyzing China’s potential to become a world leader in AI—or in any technology that requires consistent innovation—from multiple angles provides a more nuanced picture of its strengths and limitations. In a June 2020 article in Foreign Affairs, Oxford fellows Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osborne argued that China’s big advantages may not actually be that advantageous in the long run—and its limitations may be very limiting.

Moving the AI Needle

To get an idea of who’s likely to take the lead in AI, it could help to first consider how the technology will advance beyond its current state.

To put it plainly, AI is somewhat stuck at the moment. Algorithms and neural networks continue to achieve new and impressive feats—like DeepMind’s AlphaFold accurately predicting protein structures or OpenAI’s GPT-3 writing convincing articles based on short prompts—but for the most part these systems’ capabilities are still defined as narrow intelligence: completing a specific task for which the system was painstakingly trained on loads of data.

(It’s worth noting here that some have speculated OpenAI’s GPT-3 may be an exception, the first example of machine intelligence that, while not “general,” has surpassed the definition of “narrow”; the algorithm was trained to write text, but ended up being able to translate between languages, write code, autocomplete images, do math, and perform other language-related tasks it wasn’t specifically trained for. However, all of GPT-3’s capabilities are limited to skills it learned in the language domain, whether spoken, written, or programming language).

Both AlphaFold’s and GPT-3’s success was due largely to the massive datasets they were trained on; no revolutionary new training methods or architectures were involved. If all it was going to take to advance AI was a continuation or scaling-up of this paradigm—more input data yields increased capability—China could well have an advantage.

But one of the biggest hurdles AI needs to clear to advance in leaps and bounds rather than baby steps is precisely this reliance on extensive, task-specific data. Other significant challenges include the technology’s fast approach to the limits of current computing power and its immense energy consumption.

Thus, while China’s trove of data may give it an advantage now, it may not be much of a long-term foothold on the climb to AI dominance. It’s useful for building products that incorporate or rely on today’s AI, but not for pushing the needle on how artificially intelligent systems learn. WeChat data on users’ spending habits, for example, would be valuable in building an AI that helps people save money or suggests items they might want to purchase. It will enable (and already has enabled) highly tailored products that will earn their creators and the companies that use them a lot of money.

But data quantity isn’t what’s going to advance AI. As Frey and Osborne put it, “Data efficiency is the holy grail of further progress in artificial intelligence.”

To that end, research teams in academia and private industry are working on ways to make AI less data-hungry. New training methods like one-shot learning and less-than-one-shot learning have begun to emerge, along with myriad efforts to make AI that learns more like the human brain.

While not insignificant, these advancements still fall into the “baby steps” category. No one knows how AI is going to progress beyond these small steps—and that uncertainty, in Frey and Osborne’s opinion, is a major speed bump on China’s fast-track to AI dominance.

How Innovation Happens

A lot of great inventions have happened by accident, and some of the world’s most successful companies started in garages, dorm rooms, or similarly low-budget, nondescript circumstances (including Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Apple, to name a few). Innovation, the authors point out, often happens “through serendipity and recombination, as inventors and entrepreneurs interact and exchange ideas.”

Frey and Osborne argue that although China has great reserves of talent and a history of building on technologies conceived elsewhere, it doesn’t yet have a glowing track record in terms of innovation. They note that of the 100 most-cited patents from 2003 to present, none came from China. Giants Tencent, Alibaba, and Baidu are all wildly successful in the Chinese market, but they’re rooted in technologies or business models that came out of the US and were tweaked for the Chinese population.

“The most innovative societies have always been those that allowed people to pursue controversial ideas,” Frey and Osborne write. China’s heavy censorship of the internet and surveillance of citizens don’t quite encourage the pursuit of controversial ideas. The country’s social credit system rewards people who follow the rules and punishes those who step out of line. Frey adds that top-down execution of problem-solving is effective when the problem at hand is clearly defined—and the next big leaps in AI are not.

It’s debatable how strongly a culture of social conformism can impact technological innovation, and of course there can be exceptions. But a relevant historical example is the Soviet Union, which, despite heavy investment in science and technology that briefly rivaled the US in fields like nuclear energy and space exploration, ended up lagging far behind primarily due to political and cultural factors.

Similarly, China’s focus on computer science in its education system could give it an edge—but, as Frey told me in an email, “The best students are not necessarily the best researchers. Being a good researcher also requires coming up with new ideas.”

Winner Take All?

Beyond the question of whether China will achieve AI dominance is the issue of how it will use the powerful technology. Several of the ways China has already implemented AI could be considered morally questionable, from facial recognition systems used aggressively against ethnic minorities to smart glasses for policemen that can pull up information about whoever the wearer looks at.

This isn’t to say the US would use AI for purely ethical purposes. The military’s Project Maven, for example, used artificially intelligent algorithms to identify insurgent targets in Iraq and Syria, and American law enforcement agencies are also using (mostly unregulated) facial recognition systems.

It’s conceivable that “dominance” in AI won’t go to one country; each nation could meet milestones in different ways, or meet different milestones. Researchers from both countries, at least in the academic sphere, could (and likely will) continue to collaborate and share their work, as they’ve done on many projects to date.

If one country does take the lead, it will certainly see some major advantages as a result. Brookings Institute fellow Indermit Gill goes so far as to say that whoever leads in AI in 2030 will “rule the world” until 2100. But Gill points out that in addition to considering each country’s strengths, we should consider how willing they are to improve upon their weaknesses.

While China leads in investment and the US in innovation, both nations are grappling with huge economic inequalities that could negatively impact technological uptake. “Attitudes toward the social change that accompanies new technologies matter as much as the technologies, pointing to the need for complementary policies that shape the economy and society,” Gill writes.

Will China’s leadership be willing to relax its grip to foster innovation? Will the US business environment be enough to compete with China’s data, investment, and education advantages? And can both countries find a way to distribute technology’s economic benefits more equitably?

Time will tell, but it seems we’ve got our work cut out for us—and China does too.

This article first appeared on Singularity Hub and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Image Credit: Adam Birkett on Unsplash

Science and Technology

‘The Social Dilemma’ Will Freak You Out—But There’s More to the Story

Is social media ruining the world?

Dramatic political polarization. Rising anxiety and depression. An uptick in teen suicide rates. Misinformation that spreads like wildfire.

The common denominator of all these phenomena is that they’re fueled in part by our seemingly innocuous participation in digital social networking. But how can simple acts like sharing photos and articles, reading the news, and connecting with friends have such destructive consequences?

These are the questions explored in the new Netflix docu-drama The Social Dilemma. Directed by Jeff Orlowski, it features several former Big Tech employees speaking out against the products they once upon a time helped build. Their reflections are interspersed with scenes from a family whose two youngest children are struggling with social media addiction and its side effects. There are also news clips from the last several years where reporters decry the technology and report on some of its nefarious impacts.

Tristan Harris, a former Google design ethicist who co-founded the Center for Humane Technology (CHT) and has become a crusader for ethical tech, is a central figure in the movie. “When you look around you it feels like the world is going crazy,” he says near the beginning. “You have to ask yourself, is this normal? Or have we all fallen under some kind of spell?”

Also featured are Aza Raskin, who co-founded CHT with Harris, Justin Rosenstein, who co-founded Asana and is credited with having created Facebook’s “like” button, former Pinterest president Tim Kendall, and writer and virtual reality pioneer Jaron Lanier. They and other experts talk about the way social media gets people “hooked” by exploiting the brain’s dopamine response and using machine learning algorithms to serve up the customized content most likely to keep each person scrolling/watching/clicking.

The movie veers into territory explored by its 2019 predecessor The Great Hack—which dove into the Cambridge Analytica scandal and detailed how psychometric profiles of Facebook users helped manipulate their political leanings—by having its experts talk about the billions of data points that tech companies are constantly collecting about us. “Every single action you take is carefully monitored and recorded,” says Jeff Siebert, a former exec at Twitter. The intelligence gleaned from those actions is then used in conjunction with our own psychological weaknesses to get us to watch more videos, share more content, see more ads, and continue driving Big Tech’s money-making engine.

“It’s the gradual, slight, imperceptible change in your own behavior and perception that is the product,” says Lanier. “That’s the only thing there is for them to make money from: changing what you do, how you think, who you are.” The elusive “they” that Lanier and other ex-techies refer to is personified in the film by three t-shirt clad engineers working tirelessly in a control room to keep peoples’ attention on their phones at all costs.

Computer processing power, a former Nvidia product manager points out, has increased exponentially just in the last 20 years; but meanwhile, the human brain hasn’t evolved beyond the same capacity it’s had for hundreds of years. The point of this comparison seems to be that if we’re in a humans vs. computers showdown, we humans haven’t got a fighting chance.

But are we in a humans vs. computers showdown? Are the companies behind our screens really so insidious as the evil control room engineers imply, aiming to turn us all into mindless robots who are slaves to our lizard-brain impulses? Even if our brain chemistry is being exploited by the design of tools like Facebook and YouTube, doesn’t personal responsibility kick in at some point?

The Social Dilemma is a powerful, well-made film that exposes social media’s ills in a raw and immediate way. It’s a much-needed call for government regulation and for an actionable ethical reckoning within the tech industry itself.

But it overdramatizes Big Tech’s intent—these are, after all, for-profit companies who have created demand-driven products—and under-credits social media users. Yes, we fall prey to our innate need for connection and approval, and we’ll always have a propensity to become addicted to things that make us feel good. But we’re still responsible for and in control of our own choices.

What we’re seeing with social media right now is a cycle that’s common with new technologies. For the first few years of social media’s existence, we thought it was the best thing since sliced bread. Now it’s on a nosedive to the other end of the spectrum—we’re condemning it and focusing on its ills and unintended consequences. The next phase is to find some kind of balance, most likely through adjustments in design and, possibly, regulation.

“The way the technology works is not a law of physics. It’s not set in stone. These are choices that human beings like myself have been making, and human beings can change those technologies,” says Rosenstein.

The issue with social media is that it’s going to be a lot trickier to fix than, say, adding seatbelts and air bags to cars. The sheer size and reach of these tools, and the way in which they overlap with issues of freedom of speech and privacy—not to mention how they’ve changed the way humans interact—means it will likely take a lot of trial and error to come out with tools that feel good for us to use without being addicting, give us only true, unbiased information in a way that’s engaging without preying on our emotions, and allow us to share content and experiences while preventing misinformation and hate speech.

In the most recent episode of his podcast Making Sense, Sam Harris talks to Tristan Harris about the movie and its implications. Tristan says, “While we’ve all been looking out for the moment when AI would overwhelm human strengths—when would we get the Singularity, when would AI take our jobs, when would it be smarter than humans—we missed this much much earlier point when technology didn’t overwhelm human strengths, but it undermined human weaknesses.”

It’s up to tech companies to re-design their products in more ethical ways to stop exploiting our weaknesses. But it’s up to us to demand that they do so, be aware of these weaknesses, and resist becoming cogs in the machine.

This article first appeared on Singularity Hub and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Image Credit: Rob Hampson on Unsplash

-

Our Mississippi Home7 days ago

Our Mississippi Home7 days agoCreate Art from Molten Metal: Southern Miss Sculpture to Host Annual Interactive Iron Pour

-

Local News6 days ago

Local News6 days agoCelebrate the holidays in Ocean Springs with free, festive activities for the family

-

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago

News from the South - Georgia News Feed6 days ago'Hunting for females' | First day of trial in Laken Riley murder reveals evidence not seen yet

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days ago

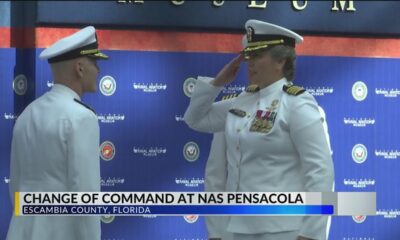

News from the South - Alabama News Feed7 days agoFirst woman installed as commanding officer of NAS Pensacola

-

Kaiser Health News4 days ago

Kaiser Health News4 days agoA Closely Watched Trial Over Idaho’s Near-Total Abortion Ban Continues Tuesday

-

Mississippi Today6 days ago

Mississippi Today6 days agoOn this day in 1972

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed2 days agoTrial underway for Sheila Agee, the mother accused in deadly Home Depot shooting

-

News from the South - Alabama News Feed2 days ago

News from the South - Alabama News Feed2 days agoAlabama's weather forecast is getting colder, and a widespread frost and freeze is likely by the …